A new approach to demographic trends in Serbia

Faced with declining population numbers, Serbia needs to redefine what it takes to be a thriving, productive society. We bring a new framing to depopulation, one of the most significant global trends of the future.

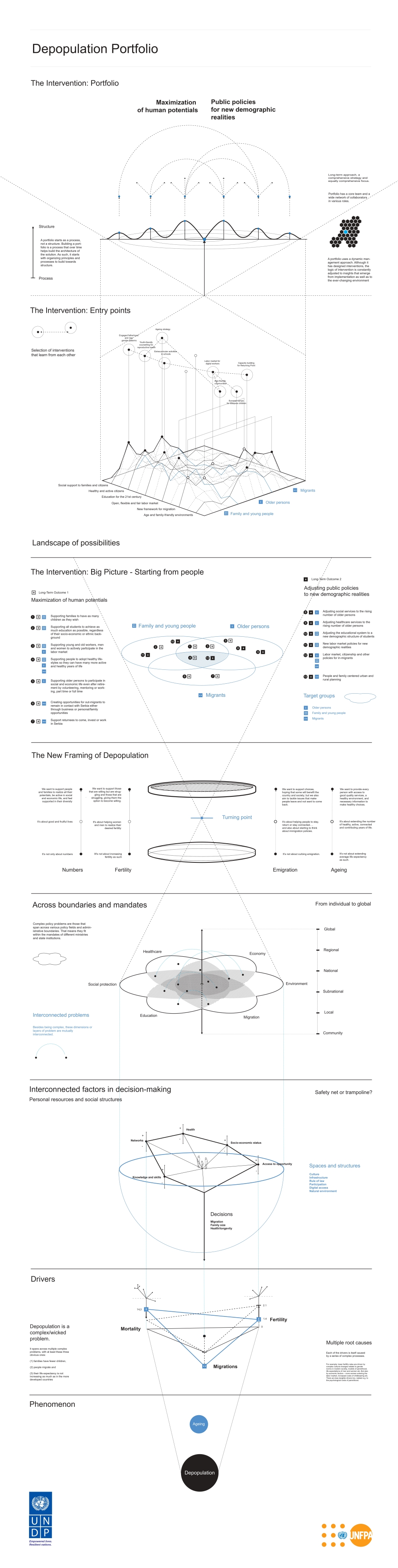

The draft of the full narrative for the portfolio is available here, and the visual representation of the approach is here. We welcome comments to both.

The approach starts with an understanding that:

- Depopulation is a serious challenge with potentially deep development repercussions. It may cause disruptions in labor, healthcare, pension, and other large public systems. It exacerbates regional developmental differences, depletes human capital for innovation and development, and changes environmental conditions in specific areas. It also brings a different composition of society, which requires adaptation.

- It is unlikely to “solve” depopulation by reversing demographic trends.

- Population change manifests in many interconnected ways that should be treated together.

- Adapting to population change is part of the future-readiness of societies, intersecting with the impact of technology, climate change, and other macro trends.

- There is an urgent need for new ways of understanding the problem and new, dynamic approaches to responding, and harnessing the opportunities that also always come with demographic change.

Responding to Depopulation

Designing a response to big, interconnected problems without real “solutions” requires systems thinking. The UNDP Accelerator Lab works with partners in all spheres to apply systems thinking and lead a process of discovery. Bringing new lenses to entrenched problems and basing a response in existing complex dynamics opens new strategic possibilities.UNFPA has over 50 years of experience in advising governments on demographic change. Demographic change always brings challenges and opportunities. What is needed to make a society resilient to demographic change is a comprehensive policy mix that is people centered and grounded in evidence. Demographically resilient societies understand and anticipate the population dynamics they are experiencing; they mitigate the negative and harness the positive effects of demographic change.

What is the problem?

All of the countries experiencing sustained population decline over the last 30 years are in Eastern Europe, including Serbia. This is a unique regional challenge, and there is no global “best practice” or any real precedent.

And while all demographic projections indicate long-term decline, it isn’t easy to get exact measurements of change.

Current policy approaches typically focus on reversing or reducing demographic trends, such as giving incentives for increasing the birth rate or reversing emigration. This is a very narrow maneuvering space, with little long-term evidence of success so far.

Population shrinking comes with qualitative changes too. The future population is not only smaller, but also older, more urban, and concentrated in specific parts of the country. It is also likely to be wealthier, more internationally connected, and more skilled. How do we adapt to provide most opportunity to this future society?

What is causing it?

The basic driving forces of depopulation are clear:

- The number of people born each year is lower than the number of people who die (the difference between fertility and mortality), and

- More people leave the country each year than come in or come back (net emigration).

This translates into three factors: fertility, morality and migration.

Fertility. The number of live births per woman completing her reproductive life (the total fertility rate) is declining in many parts of the world. In Serbia, it has been under the level of reproduction (2.1) since the middle of the 20th century, and stood at 1.5 in 2019.

There is no simple scientific explanation for this: lower total fertility rates are partly due to delayed parenthood, and partly driven by complex cultural changes, gender norms, opportunities for youth, models of parenthood, life expectations of men and women, economic factors and labor market conditions, costs of childbearing, etc. There is no single factor that could be altered to cause a predictable change in the outcome.

Mortality. Serbia’s population has around 5 years lower life expectancy compared to the EU, despite an increase over the last two decades. We are living longer but this progress has mainly been achieved by reducing child mortality rather than through life extension.

There are multiple dimensions involved here, such as the prevalence of risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases, availability of healthcare services, environmental conditions, nutritional habits, and other healthy life choices. No single intervention could hope to improve overall population health.

Migration. Serbia is traditionally an emigration country, with OECD estimating over 650,000 people to have left Serbia in the last two decades. Most of this is qualified as “economic migration”, driven by lower salaries compared to Western markets.

But like other drivers of depopulation, migration reflects all the complexity of human decision-making and is shaped by more than the economic or political environment. Established cultural practices and social norms play a role, with emigration still the equivalent of “success” and return perceived as “failure”.

Accession to the EU accelerated similar trends in countries in the region. On the other hand, new technology and cost of transport benefit the rise of circular and other new types of migration.

A wicked problem

This makes depopulation a wicked problem. It has no clear end-point: there is no optimal population size, just as there is no optimal life expectancy or migration level. Improvements in the system will be interpreted differently based on the value system applied.

Sticking with a merely quantitative definition of the problem leaves a very narrow space for action.

Starting from a human perspective

In good part, depopulation is the result of a collection of decisions people take on some of the most intimate aspects of their lives. Where to live and whether to return, whether to have a family (of what size and at what age?), and the series of healthy or unhealthy choices that ultimately determine how long we live.

The “trampoline” we stand on comprises various personal resources that give or deny opportunity, where choices are made by us or for us.

These are further shaped by the spaces and structures in which we live – the broader culture and environment that explicitly or implicitly facilitate certain choices instead of others.

Integrated policy space

The interconnected nature of the challenge reflects back on the institutional and policy setup – depopulation does not neatly fit into a sectoral box. Instead, it spans across various policy fields and administrative boundaries, fitting within the mandates of numerous ministries and state institutions.

This means that it is not easy for governments to address. Single-point solutions that target a particular cause in one domain will not necessarily have the intended effects in other domains.

Moreover, these linkages will play out differently on different levels of organization – from community to global.

Complex problems require broad and sometimes untraditional partnerships.

The New Framing of Depopulation

We propose a new framing of depopulation. It respects the complex and interconnected nature of the challenge, and significantly broadens the space for action.

The new framing takes two critical lenses to the challenge: an ethical lense, whereby any action should embrace the highest standards of human rights and liberties, and a reality lense, whereby action needs to be feasible in the current institutional and legal setup and with available resources.

Numbers

It’s not only about numbers.

It’s about good and fruitful lives.

We want to support people and families to realize all their potentials, be active in social and economic life, and feel supported in their diversity.

Fertility

It’s not about increasing fertility as such.

It’s about helping women and men to realize their desired fertility.

We want to support those that are willing but are struggling and those that are struggling, giving them the option to become willing.

Emigration

It’s not about curbing emigration.

It’s about helping people to stay, return or stay connected… and also about starting to think about immigration policies.

We want to support choices, hoping that some will benefit the country and society; but we also aim to tackle issues that make people leave and not want to come back.

Ageing

It’s not about extending average life expectancy as such.

It’s about extending the number of healthy, active, connected and contributing years of life.

We want to provide every person with access to good quality services, a healthy environment, and necessary information to make healthy choices and to continue actively contributing to economic and public life.

The north stars

With this framing in mind, it makes sense to orient action towards two desired effects:

- Maximization of human potential

- Adaptiveness of public policies to new demographic realities.

The Intervention: Big Picture

These long-term effects are translated into possible actions from the perspective of three target groups: families and youth, older persons, and migrants (including diaspora).

A wide range of specific interventions towards the two “north stars” is conceivable for each target group, or for all of them. The concrete sets of actions taken will be context-specific, integrated, and designed as leverage points

The Intervention: Landscape of Possibility

The new framing of depopulation results in an entire landscape of possibility.

This space is potentially infinite, and the portfolio does not attempt to cover all of it. It is also evolving and mutable - different areas will show different amounts of energy at different points in time.

The portfolio should, over time, strive to discover the different forces at play.

The intervention: entry points

Entry points – specific strategic interventions in the system – serve as a vehicle for moving through the landscape.

Shifting complex social or institutional ecosystems requires multiple sets of interconnected interventions that learn from each other. They need to work in positive sum to drive different parts of the system towards a preferred reality over time. Entry points should be designed to connect with and unlock new areas of the landscape, enabling further interventions.

They will be context-specific and should represent the diversity of strategic “bets” to be tested through a portfolio.The entry points provided in the full narrative and visual description of the portfolio are illustrative of our analyses and actions so far.

The Intervention: Portfolio

The sets of interventions that act together and learn from each other is the Depopulation Portfolio.

The objective – to shift an entire complex system towards an alternative, preferred reality – needs an approach that is respectful of its ambition. The portfolio is therefore not a set of smart actions on a common theme. It is the system of interconnected actions designed to benefit learning about a complex system that is capable of continuously evolving and adapting to changing realities.

Learn more and contribute

The draft of the full narrative for the portfolio is available here, and the visual representation of the approach is here. Our work will benefit from your comments! Feel free to make suggestions in the document, or get in touch with us [lab.rs@undp.org; serbia.office@unfpa.org ].